Here’s a purely hypothetical question for you. Let’s suppose you have a certain number of hospital beds and a certain number of ventilators and a certain number of medical staff. Further, let’s suppose that there are more sick people than there are beds, ventilators, and staff. The system has insufficient capacity to meet the need. Or, in economic terms, demand exceeds supply. How do you determine who receives help?

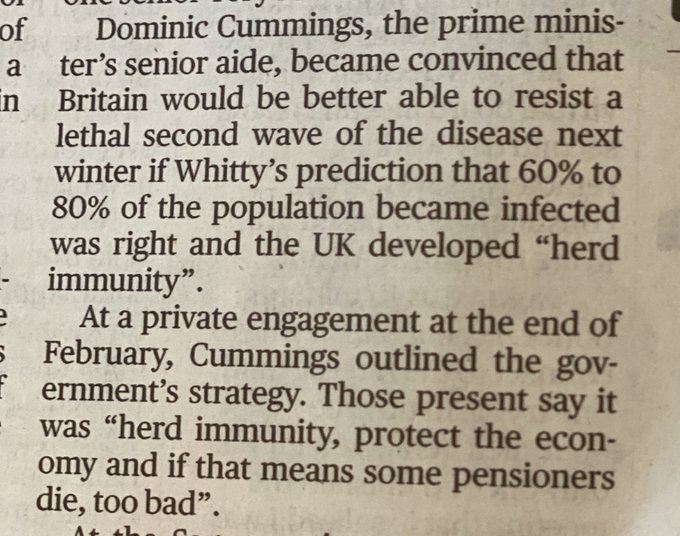

That question of triage, deciding who is to die, is a difficult moral calculus–for some people. For eugenicists or Nazis, it’s not: kill the old and feeble, the physically or mentally deranged, the scum; cull the weak from the herd and improve the species. Or, as Dominic Cummings, aide to Boris Johnson, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, put it: “if that means some pensioners die, too bad.“

Each time the United States argues over a national health care system, someone attempts to assert that socialized medicine leads inevitably to death panels, as if rationing life by one’s ability to pay were more humane than a committee. The thought was that at some point the State would decide it’s just too expensive to keep Granny alive and she would be killed–completely ignoring the fact that Congress funds anything out of nothing more than desire.

Yet somehow refusing to order production of medical equipment or prepare for a pandemic does not rise to the same level of callousness. Somehow seeking to profit from the deaths of thousands is just good business. Those actions cause or exacerbate shortages which lead to deciding who will die.

The response to COVID-19 is in a very real sense a logistics problem, in terms of delivering care to the people who need it. But it’s also one of meeting demand. And in that respect economics can offer some ways to think about it, as the field is, after all, concerned with how finite resources are allocated–the case of surge pricing toilet paper to prevent hoarding comes to mind. Though it seems rather insane for the price of N95-rated masks to have jumped from $0.70 to $7.00 each over the past week, the prices reflect a case of insufficient supply available for the demand. Some people, such as New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo, redirected existing labor to another task: making hand sanitizer. The Army Corps of Engineers are doing what they do. Others are simply volunteering to help, whether in 3-D printing a valve for a ventilator, or providing patent-free CAD designs, or manufacturing, or sewing.

The response to COVID-19 is also an ethical problem. Most people want to help; the rest are outside society.

R. R. Reno, the editor of First Things, has been on a tear recently. He’s very upset that Roman Catholic churches, among others, suspended public celebration of the Eucharist, and argues that the Church could find other ways of adjusting without shutting out the parishioners. (I suspect he might agree with me about locking the sanctuary doors.) There is something quite magical about gathering together, but expecting others to risk their lives so you can receive the Eucharist seems the opposite of courage in the face of death. Perhaps the Catholic churches could find ways to remain open, but they have decided to help prevent the spread of disease by asking their flock to worship at home, not unlike the early Christians. Some non-denominational churches, more arrogant, won’t raise no pansies.

Mr. Reno also worries about the shrinking of our social life:

[R]estrictions on public gatherings have paused institutional life. There are no Boy Scout meetings, no Little League practices, no Rotary Club or Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. Most book clubs are suspending their evening discussions, even though these small gatherings are permitted. Closed restaurants dissolve informal coffee klatches. Some institutions, organizations, and fellowships will rebound when the draconian limits on social life are lifted. But some will not. And the longer those limits last, the more will wither and fade away.

“Questioning the Shutdown,” R. R. Reno

First Things, March 20, 2020

But over the past few weeks, I’ve seen many people whose first response to the pending isolation was not to buy more toilet paper but to reach out to their family, to their friends, to others they hadn’t spoken with recently; was not to hide under the covers with a flashlight but to arrange online substitutes for in-person discussions. AT&T thanks you. We are a gregarious species.

I am lucky enough to be salaried. I am lucky enough to already work from home. My routine is not disturbed one bit. Except the Spring soccer season is on hold.

Others are not so lucky. Staying home, or, more precisely, away from work, has immediate costs that they cannot recoup. They have no help. The financial situation of many households is precarious. The financial situation of many businesses is precarious, even larger businesses. We are, the bulk of us, over-extended, living hand to mouth. Cash money is, these days, what we need to live. We may adjust to having less. Or we may die.

The financial markets, despite their formerly rosy numbers, are an illusion. The real economy always involves real people, real joy and real suffering, real living and real dying. What are we doing for real people?

We are all looking for a middle ground here, between the Scylla of mass death and the Charybdis of economic apocalypse. At this stage of the crisis, it looks like there is no middle ground. This is an intolerable thing, but it might well be reality.

“The Hard Road Ahead,” Rod Dreher,

The American Conservative, March 20, 2020

Where we devote our attention, where we give our time, and what we spend money on tells us a lot about our priorities. We have choices to make.

Meanwhile, it appears we won’t have to worry about missing Easter services. The President thinks we can open up for business in just a few days.